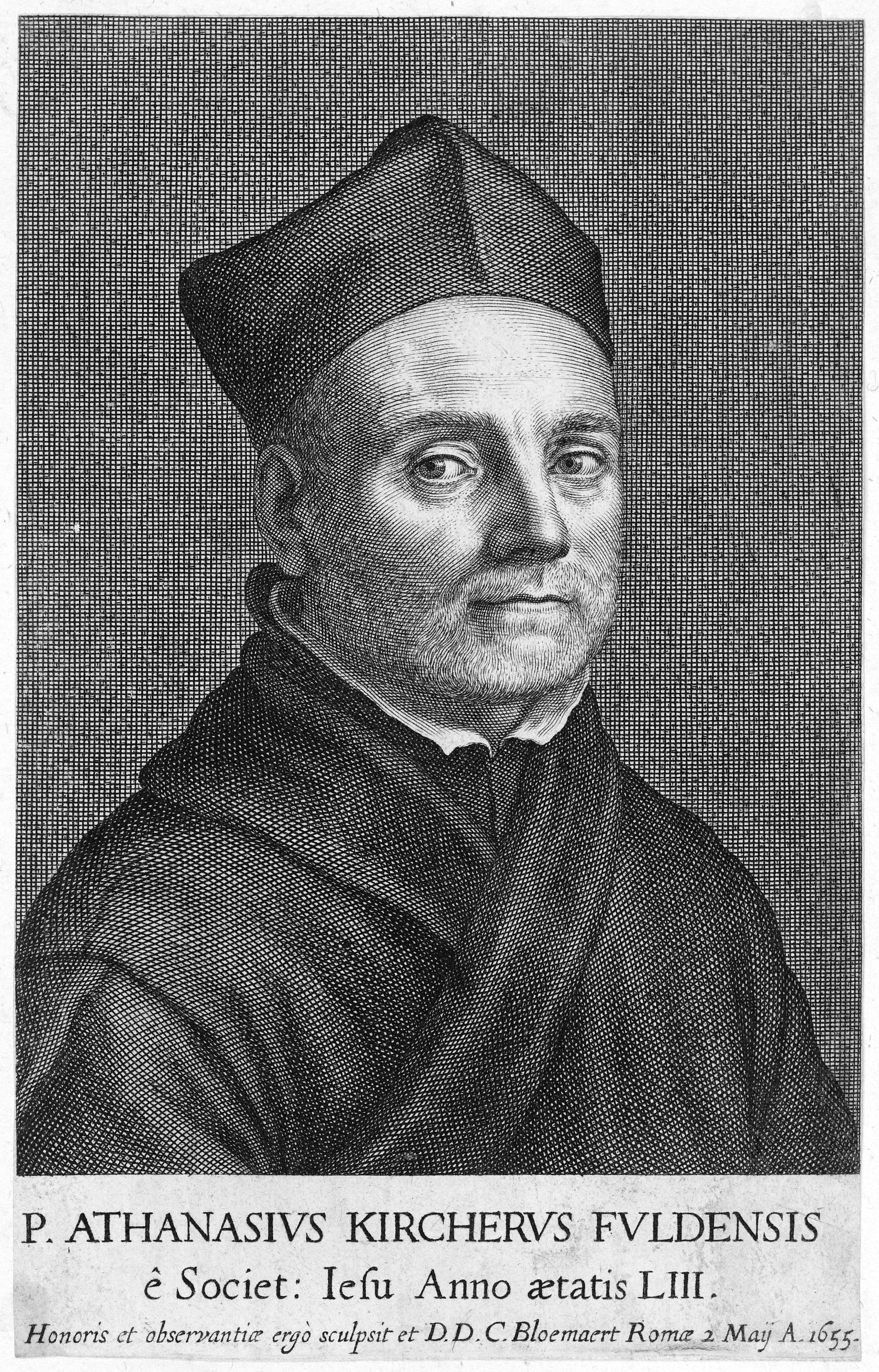

A Jesuit’s Letters: Athanasius Kircher’s Correspondence Visualized

Paula Findlen, Iva Lelková, and Suzanne Sutherland

The work presented here is part of the original “Mapping the Republic of Letters” project, which started in 2008. The goal of that project was to use data visualizations to get a better sense of the overall shape and structure of early modern networks, especially through correspondence. In the case of Kircher, we wanted to make new use of an existing digital manuscript archive, the Athanasius Kircher Correspondence Project. Developed initially by Michael John Gorman and Nick Wilding, this project began as a collaboration betweenMuseo Galileo in Florence, the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome, and the European University Institute in Fiesole. In September 2000, Stanford University Library became a partner and host of the enhanced website containing Kircher’s surviving papers in the Pontifical Gregorian University Archive. The information in this archive was the starting point for our research.

The current team, Iva Lelková, Suzanne Sutherland, and Paula Findlen, created a database from this digital archive, enriching it with geographic and prosopographic information. Under Lelková’s leadership, in 2015 we published this enriched database through Early Modern Letters Online sponsored by Oxford’s Cultures of Knowledge project. 2,693 of the letters are from Kircher’s own correspondence, with 2,260 housed in the archives of the Pontifical Gregorian University and 433 in other repositories throughout the world; 55 documents are related letters that ended up in Kircher’s surviving papers in this major Jesuit archive. We have also catalogued Kircher’s printed letters, only some of which survive in manuscript, to create a more comprehensive archive with which to produce visualizations.

Thanks to two grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, we refined and revised our data visualization techniques; the result of this process was Palladio, a suite of data visualization tools that anyone can use.

This project will visualise the communities that Locke communicated with, and show the connections within those communities. Whether writing to puritans, theologians, astronomers, arabists, alchemists, tutors, or other doctors, Locke was often a unique connector between otherwise isolated bodies of scholarly and professional expertise, religious feeling, and scientific enquiry. Through Locke’s connections to some of the most famous and influential men and women in the country – like John and Sarah Churchill, the future Duke and Dutchess of Marlborough, or Thomas Tension, the Archbishop of Canterbury – Locke helped to unite the private intellectual foments of the early British Enlightenment and worked to build from them a single public.

On this page, you will find links to Palladio elements (“bricks”) populated with data from Kircher’s correspondence. We have used the Kircher visualizations to study different elements of the patterns of his correspondence – his Bohemian network and strong ties to Central Europe, his ongoing relations with Tuscan scholars who connected Rome and Florence, and his global missionary correspondence. Our findings can be read in the articles linked below. We are making the data visualizations (as well as the data) available to other scholars so they can explore and analyze the data according to their own interests.

Mapping the Republic of Letters Project

Mapping the Republic of Letters has been an exciting collaboration for us, as well as an ongoing experiment in how to conduct collaborative, interactive historical research in a digital age. To learn more about that project, visit republicofletters.stanford.edu.