- Lead: Caroline Winterer

- Start Date: September 2008

- Team: Claire Rydell (2010 - present)

Hannah Marcus (2011 - present)

Julia Mansfield (2008 - 2011)

Scott Spillman (2008 - 2012)

Like other Mapping the Republic of Letters projects, ours has included numerous phases. One of the first issues we confronted as early as 2008 was the need to limit our scope in terms of the volume of letters we dealt with at one time. After a few years of careful and copious data transcription of the over 15,000 letters that Benjamin Franklin either wrote or received over the course of his life, the entirety of Franklin’s correspondence proved too large a mapping endeavor for our first go at it. At this point, we stepped back to examine our goals for converting Franklin’s correspondence into “data” (the easily computer-digested dates, correspondents, locations of letters sent and received). What questions did we hope to answer by compiling such “data” from Franklin’s letters? Did such questions lend themselves to an examination of a smaller set of letters?

After much deliberation, the Franklin team decided to limit our focus—for the time being—to the years between 1756 and 1763 when Franklin traveled to England and Scotland for the first time (Franklin sailed in 1757, but we extended our focus to a few month before and after his six year trip). The years between 1756/7-1762 were an exciting and formative moment in Franklin’s life. During these years, Franklin met many leading intellectual luminaries of his day, including David Hume and Lord Kames. In the two years since we began the intensive processing of Franklin’s correspondence between 1756 and 1763, we have formulated new and important questions about the nature of Franklin’s correspondence network—questions that lend themselves to the deeper and more precise nature of our investigation now structured around Franklin’s first trip to London.

These explorations have also lent themselves to thinking broadly about the republic of letters and where the Americas fit into it. For an in-depth survey of these matters, see: Caroline Winterer, “Where is America in the Republic of Letters?” Modern Intellectual History 9, 3 (Nov. 2012): 597-623.

Current Goals and Interests of the Project

Using the collection of Franklin's correspondence found online, we extracted from Franklin's correspondence the following information about each letter: its date, its author and recipient and their genders, communities (aka “professions” in an eighteenth-century sense of the word), and places of birth; its source location and the location of its recipient. Once we had this information from each letter, we could shift our attention from the physical letters (Franklin’s correspondence) to the people behind the letters (Franklin’s correspondents) By engaging both with the letters and the people writing and receiving the letters, our team could formulate and answer two sets of questions: (type 1) those about the physical letters themselves and (type 2) those about the correspondents of whom Franklin’s correspondence network was comprised between 1756-1763. Thinking about Franklin’s correspondents themselves required that we separate out each individual correspondent from the “letters” spreadsheet to create a separate “individuals” spreadsheet. Armed with these two spreadsheets, we could begin the process creating computer-generated visualizations that enabled us to formulate and begin to answer very specific questions about the nature of Franklin’s correspondence and correspondents network.

A few examples of type 1 questions with some preliminary conclusions reached by examining visualizations from the “letters” spreadsheet:

During what months did Franklin receive letters from particular locations (i.e. England, Scotland, and America) and how did the numbers of letters from one location relate proportionally to letters from other locations?

One conclusion drawn:

- In December 1756, before Franklin set sail for London, 100% of letters he received came from America.

- In January 1762, when Franklin is overseas, 100% of letters he received came from England.

- In December 1763, when Franklin had returned from London, over 75% of letters Franklin received were from America.

When did Franklin receive letters from Scotland?

Franklin received letters from Scotland in only four months between 1757-1763: in September 1759, October 1759, March 1761, and May 1762

From what countries did Franklin receive most of his letters between 1757 and 1763?

Franklin received nearly all his letters from two places: British America and England. Very few other places are represented, challenging us to think about the timing of Franklin’s ascent into the ranks of the “cosmopolitan” on the world stage

A few examples of type 2 questions with some preliminary conclusions reached by examining visualizations from the “correspondents” spreadsheet:

Who were Franklin’s top correspondents by volume of correspondence?

- Isaac Norris

- Mary Stevenson

- David Hall

- Deborah Franklin

William Strahan

Grouped by gender, who were Franklin’s top correspondents?

- Male: Isaac Norris, David Hall, William Strahan, Peter Collinson

- Female: Mary Stevenson, Deborah Franklin, Jane Mecom, Elizabeth Graeme

Grouped by country of birth, who were Franklin’s top correspondents?

- David Hall and William Strahan appear to be Franklin’s top two “Scottish” correspondents, but neither one actually lived in Scotland at the time of Franklin’s trip there.

- Mary Stevenson, the daughter of Franklin’s London landlady, Margaret Stevenson is Franklin’s top “English”correspondent during this time.

With what community association or professional group did Franklin correspond the most? (Top five)

- professionals

- secular officials

- professionals and secular officials

- artisans

- church officials

Where do women rank in his network?

Franklin wrote most of his letters to men.

With these conclusions from the visualizations of Franklin’s correspondence network, our team is generating a second set of questions, which will result in a new interpretation of Franklin’s presence on the world stage during this first trip to London.

Initial Question Answers from the visualizations of the data Level 2 Question inspired by the Answers from the Initial Question Interpretative Conclusions about the Level 2 question that help us understand Franklin in the context of his eighteenth century world.

Defining Terms: “Cosmopolitanism”

Some of the level 2 questions we are engaging with now include the following: To what extent was Benjamin Franklin a “cosmopolitan” and how might we begin to define this term for maximum analytic utility during the eighteenth century? What can Franklin’s correspondence network tell us about the relationship between centers and peripheries in the eighteenth century? Are there significant or tangible differences between a process of Anglicization (someone like Franklin in a colonial periphery engaging more with and becoming integrated into centers like London and Edinburgh) and becoming a “cosmopolitan”?

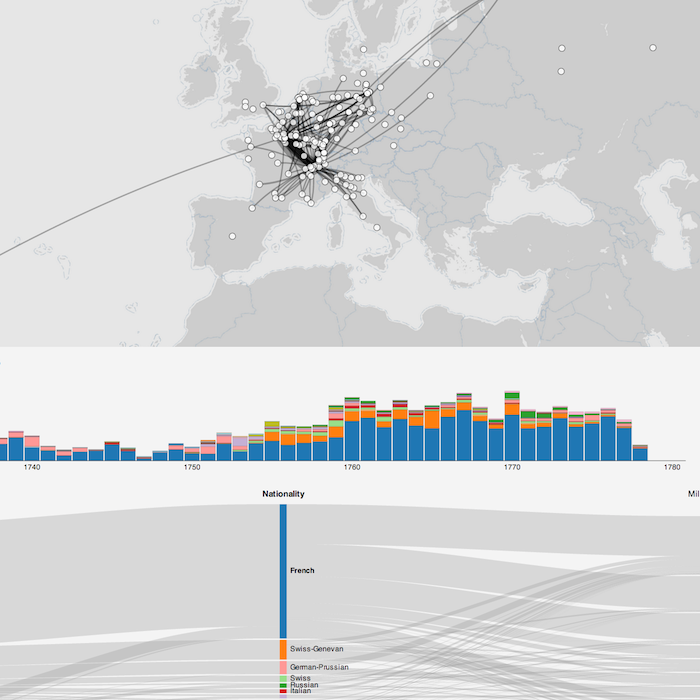

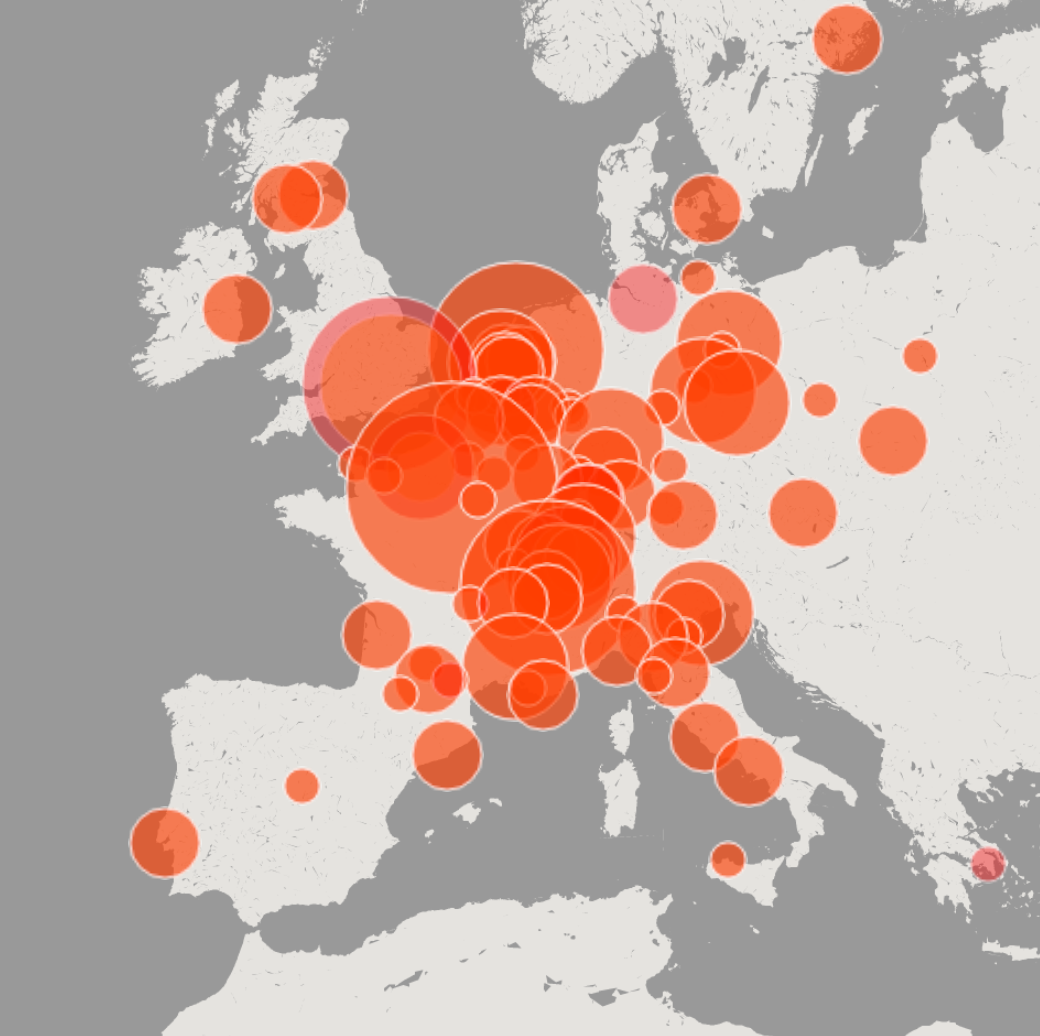

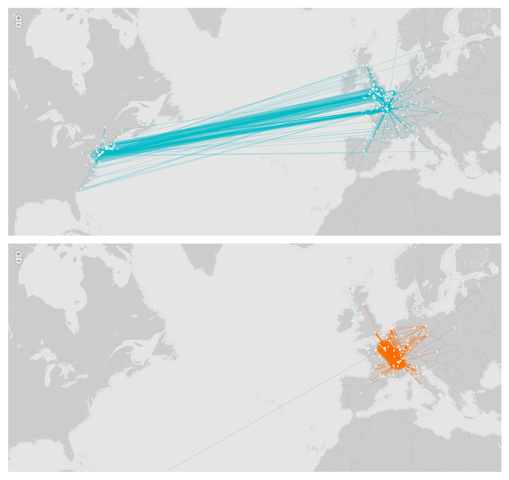

One vivid example of how Franklin’s correspondence network reveals the prospects and limits of “cosmopolitanism” is to compare it with Voltaire’s. The geomap below show Franklin’s network (top) and Voltaire’s (bottom). Many of Franklin’s letters crossed the Atlantic; only a few of Voltaire’s did. One could argue that Franklin was more cosmopolitan than Voltaire because his letter network was more trans-Atlantic; yet any scholar working in the Enlightenment would vigorously dispute that conclusion, arguing that other measures should also help us to define cosmopolitanism. Visualizations of these kinds, in short, challenge us to think about how we might define analytic terms such as “cosmopolitanism” more rigorously, including both impressionistic measures and numerical measures.

Note: Images are sketches, they need refinement and need to be checked for accuracy.

How to cite this page:

Claire Rydell and Caroline Winterer, "Benjamin Franklin's Correspondence Network, 1757-1763," Mapping the Republic of Letters Project, Stanford University, October 2012

Related

Humanities+Design

Visit the laboratory web site to learn more about the visualizations.