- Lead: Dan Edelstein

- Start Date: September 2010

- Team:

Maria Comsa

Melanie Conroy

Biliana Kassabova

Claude Willan

Chloe Edmundson

Bugei Nyaosi

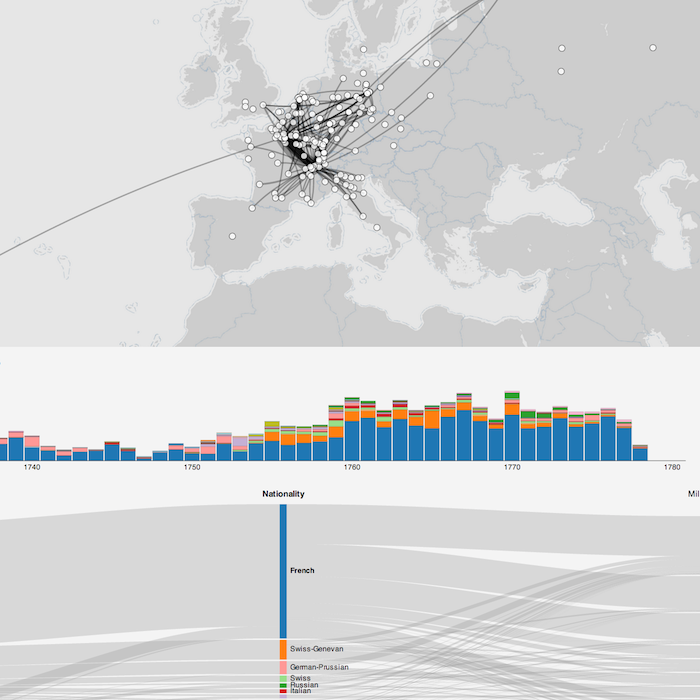

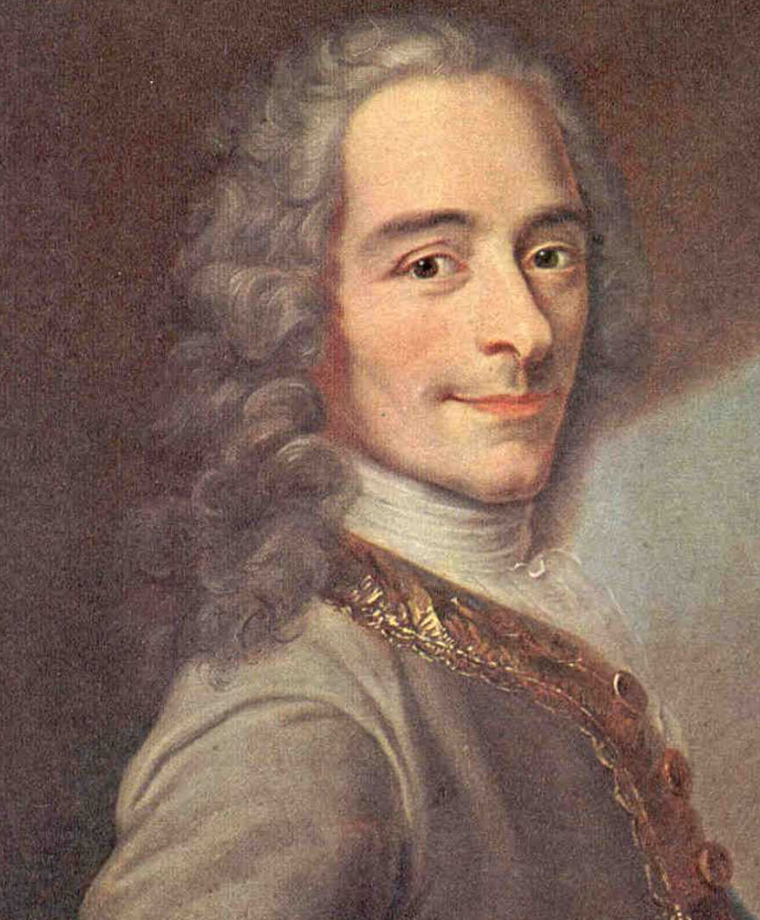

For this study, we are exploring the correspondence metadata provided to us by the [Electronic Enlightenment Project] at Oxford University. Our primary interest is in situating Voltaire’s correspondence network within the broader Enlightenment Republic of Letters. Did these networks tend to be more cosmopolitan or national? (Preliminary research suggests the latter.) What did it take to have a truly global network? (Probably an empire.) What was the role of regional correspondence? (Quite large.) What are the “coldspots” in this Republic of Letters? (For Voltaire, surprisingly, England.)

We are also exploring the social make-up of Voltaire’s correspondents. Who did he write to preferentially? What were their occupations? What was their milieu? These are some of the questions that underpinned the [visualization] we produced to explore Voltaire’s network both cartographically and socially.

Voltaire's correspondence network

While there are nearly 19,000 letters in Voltaire’s correspondence, we only have complete location data (for both sender and recipient) for about 10%. In a way, then, this map is thus doubly misleading, since ~90% of the letters are not shown, and it’s been estimated that another 50% of his letters have not been passed down. But by studying Voltaire’s correspondents, we’ve been able to show that this cartographic distribution is actually quite representative.A comparison between the correspondence networks of Locke and Voltaire

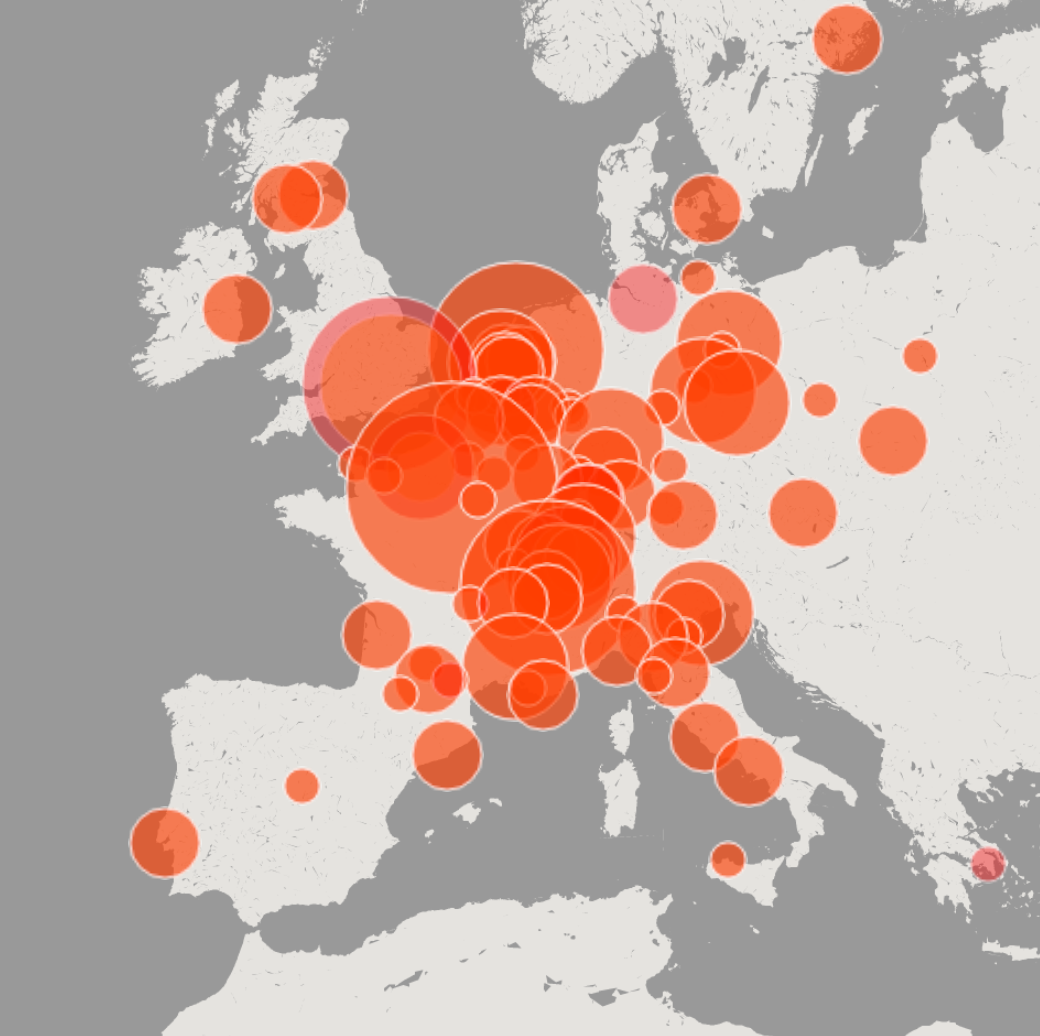

One of our first hints that Enlightenment correspondence networks may not have been as cosmopolitan as the authors liked to claim. At the same time, despite being heavily concentrated in the Anglo-Dutch area, Locke’s network stretched much farther afield, to the American colonies and to India.Range: a structural variable of correspondence networks

These different ranges can be thought of analogously to railway networks, which tend to be divided into regional, intercity, and international divisions, each of which serves a different purpose and clientele. Of course, none of these dimensions are mutually exclusive. A correspondence network can be both global and regional, both national and cosmopolitan. But as it turns out, there are far more national networks than cosmopolitan or global ones.Configuration: another structural variable of correspondence networks

We noticed that most networks have one of three configurations: axial, arterial, or radial.

An axial configuration indicates that someone is writing many letters to many people in one place; usually, this place is a capital city. In an arterial configuration, most correspondence occurs along a few major “highways.” When you look at a network over an extended time period, it tends to exhibit parallelogram forms, which comes from writing to one place while traveling.

The radial configuration is the closest to the ideal (or idealized) distribution in the Republic of letters. It generally suggests that the primary correspondent is writing a few letters to many individuals in many places. Sometimes one can find a radial configuration combined with another one: for instance, Voltaire’s correspondence network exhibits both an axial and radial structure (the “bicycle” configuration: hat tip, Caroline Winterer).

Voltaire’s Correspondents by Nationality

Although we do not have complete location data for all Voltaire’s letters, we do have good data about his correspondents. As it turns out, the vast majority of them (~70%) are French, and a similar proportion of his letters are to or from French correspondents. We can also see that while his British correspondents numbered about the same as his German or Italian ones, he exchanged far fewer letters with them (indeed, 8 times fewer letters to English than German correspondents, for instance).

Voltaire’s French Correspondents

Across the course of his long life, Voltaire continuously kept in touch with his old friends in Paris – many of whom had risen to important positions of power.

Voltaire’s British Correspondents

An interesting feature of Voltaire’s British letters is that there are only two men with whom the philosophe had a (relatively) intensive exchange. Sir Everard Fawkener – a friend from the days before Voltaire’s exile to England and to whom Zaïre is dedicated – exchanged as many as 23 letters with Voltaire over the course of fifteen years, while the correspondence with the George Keate left 38 letters exchanged in the course of twenty-one years.

Those two numbers together account for one-third of all of Voltaire’s British letters. By contrast, Voltaire’s epistolary relationship with the English contemporary great minds is quite negligible: he only wrote a few letters to Jonathan Swift (three) and Alexander Pope (two), all of them during his exile in England. Following his return to France, Voltaire does not seem to have corresponded with any English luminaries until 1763.

Voltaire's Correspondents by Milieu

To analyze the social status and position of Voltaire’s correspondents, we categorized them by milieu (allowing each correspondent to belong to up to three milieux). As we expected, a large number of them were part of “elite society”: they were gens du monde. But to our surprise, an even greater number were state officials – an indication of the tight relationship between the Enlightenment and state power.

Benjamin Franklin and Voltaire

We have no trace of letters exchanged between Voltaire and Benjamin Franklin, but the two men had many correspondents in common.